Explaining the decline in national pride in Canada

Too woken or too broken?

This year’s Canada Day holiday was met with a new round of consternation about the recent decline in the strength of national pride. The Environics Institute didn’t have brand new data to release on this topic, but I did share the most recent findings from the two surveys we’ve used to track this sentiment.

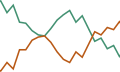

The two surveys use different question formats and cover different periods of time, but they both show that the proportion who are very proud of being a Canadian has declined by a little over 10 percentage points over the past decade.

What’s going on?

It’s tempting to speculate about the causes of this decline. I’ve succumbed to this temptation myself in previous reports (examples here, here and here). Others have weighed in too. Commentators who are more contrarian have hinted that it’s those on the political left in Canada who increasingly have recoiled from expressing pride in their country, leaving a vacuum to be filled by those on the right. This stems from the decision of the current federal government to persuade “Canadian leftists to dislike their country.” The argument is that the government’s insistence on apologizing for the country’s colonialist and racist past has convinced too many of its supporters that there is little about Canada to be proud of. The federal Liberals “have spent the last seven years actively encouraging the view that Canada is a risible country,” as the prime minister specifically decided “to make denigrating Canada central to his Liberalism.” The result is the “abandonment of Canadian nationalism to the right.”

Really?

I’ve become less sure of my own earlier explanations and more suspicious of this alternative one, so I’ve decided to dig into this question more methodically. Bear with me – this is a longer journey than usual for this newsletter, but I want to look at the issue from as many angles as possible.

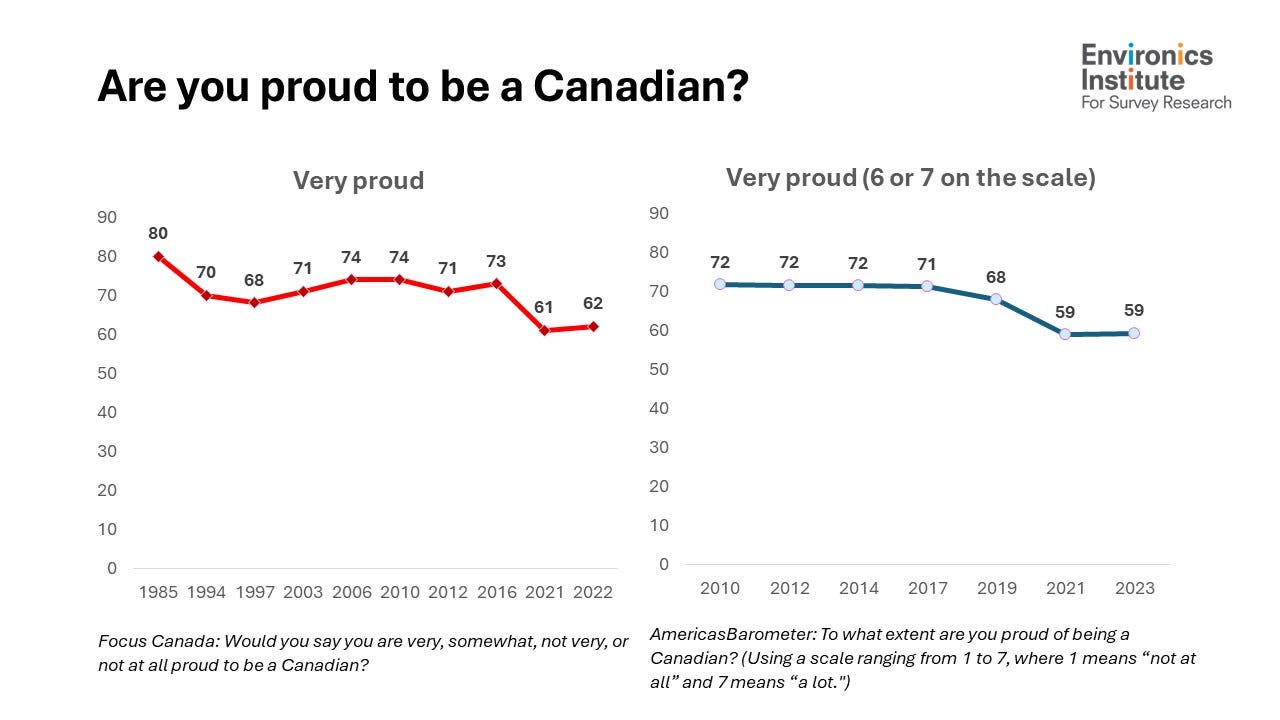

First, let’s look more closely at the change that’s taken place. The story isn’t that national pride has evaporated; it’s that the strength of pride has become more muted. The vast majority remain at least somewhat proud. Here’s the pair of charts again, casting a wider net.

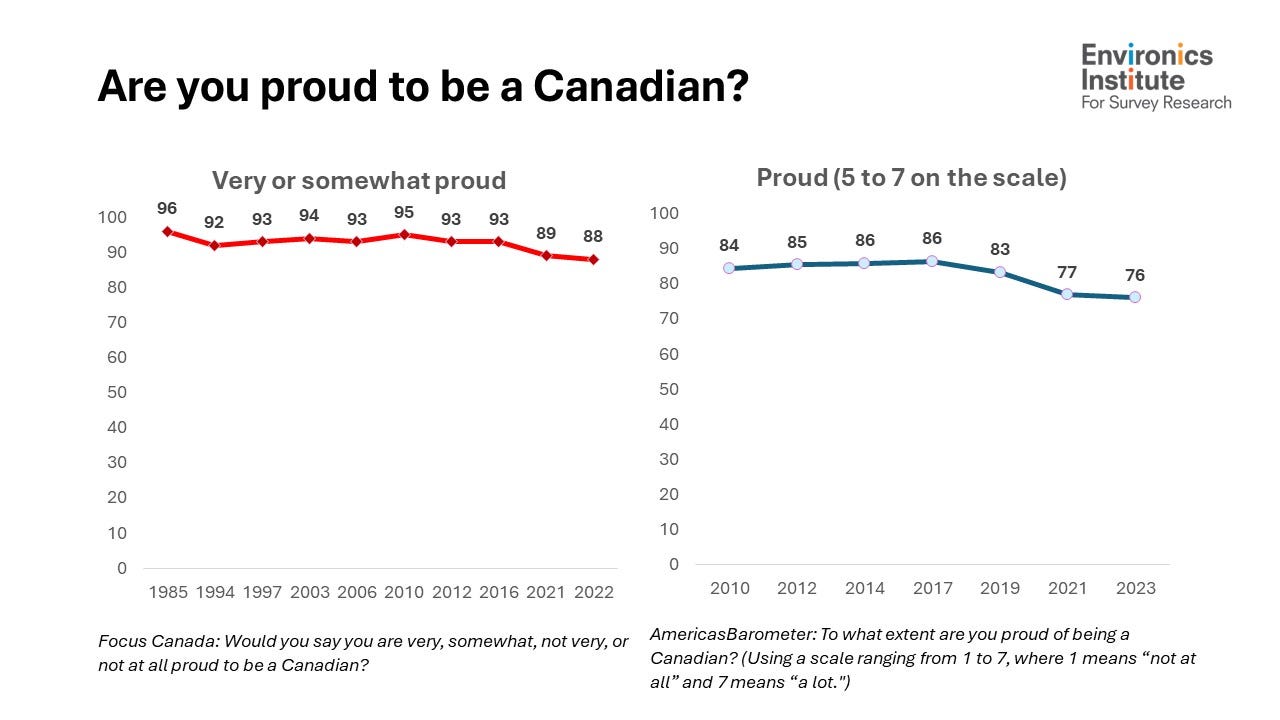

The next pair of charts shows the changes more clearly. Since 1985, the proportion strongly agreeing that they are proud to be a Canadian has dropped by almost 18 percentage points, but the proportion somewhat agreeing has seen a 10-point increase. The second survey shows an 11-point drop since 2017 in the proportion selecting the highest point on the seven-point scale, but an increase of five points in the proportion selecting the midpoint. (The proportion who are not proud to be Canadian remains small, but has edged upwards by about five to seven points depending on which question you use.)

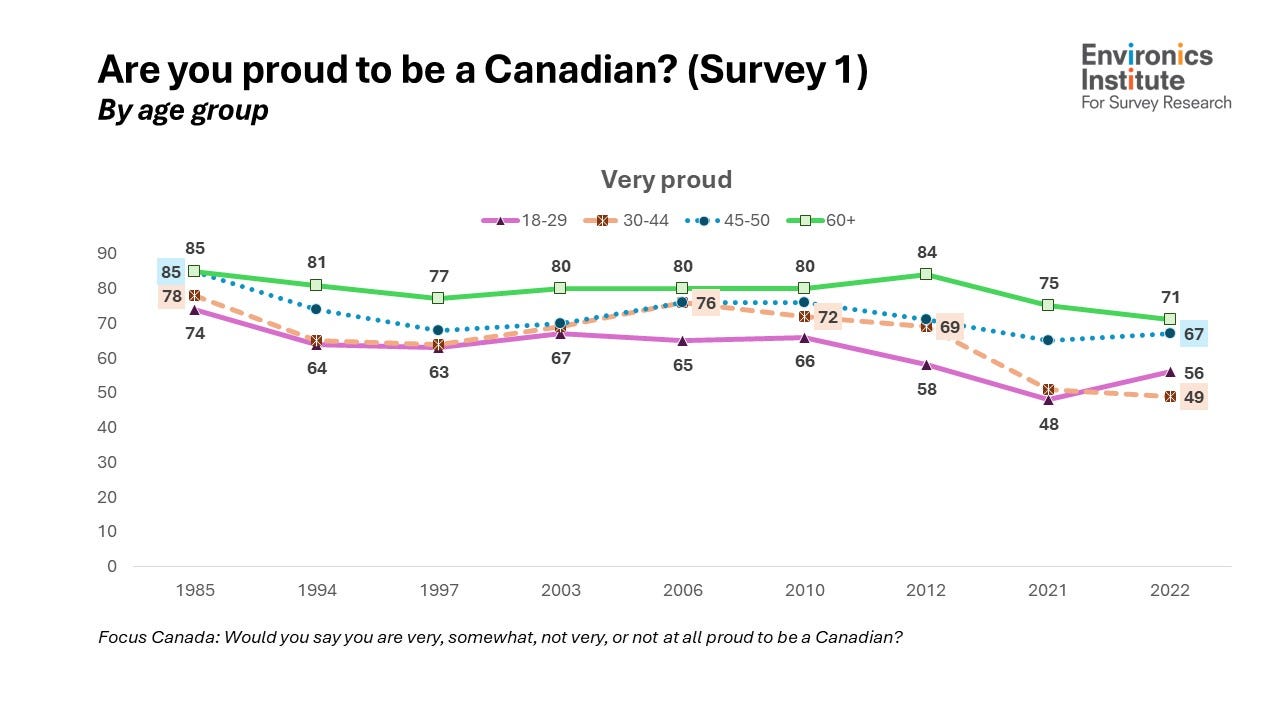

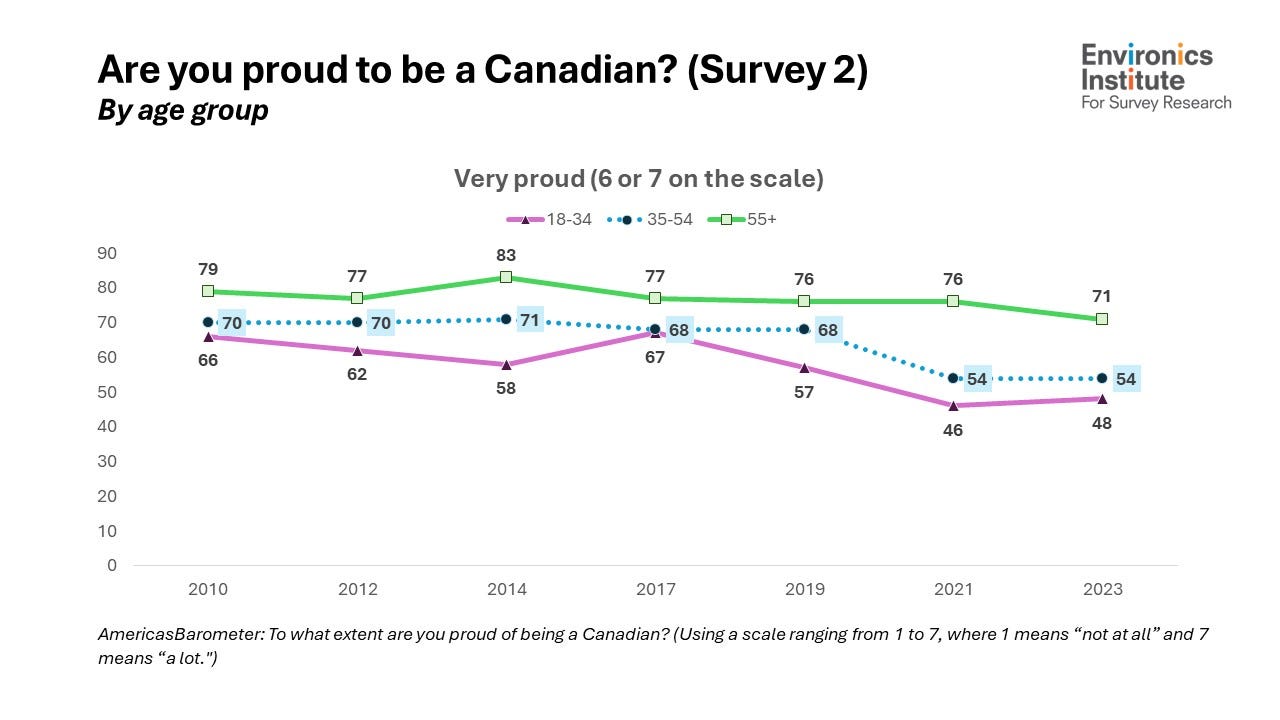

Next, we can look at the differences among age groups. Is it young Canadians, in particular, who have become less comfortable expressing a strong sense of national pride? This might be the case, for instance, if the problem lies with a shift in the school curriculum (history classes focusing less on national heroes and more on national failings), or if it’s simply the case that the youngest generation of Canadian adults – the one growing in weight as a proportion of the total population with each passing year – is simply more beholden to the alleged victimization tropes of identity politics than its predecessors.

But there’s no evidence of this. The surveys show that younger Canadians are less likely than their older counterparts to say they are very proud to be Canadian – but this is hardly new; it’s true in every year for which we have data. And, while younger Canadians are less likely to say they are very proud today than they were 10 years ago, this pattern holds for all age groups.

Whatever’s going on, it’s not primarily about younger Canadians. The most we can say is that the decline in national pride is less pronounced among older Canadians – those age 55 or 60 and older. But it covers middle-aged Canadians, who finished school decades ago.

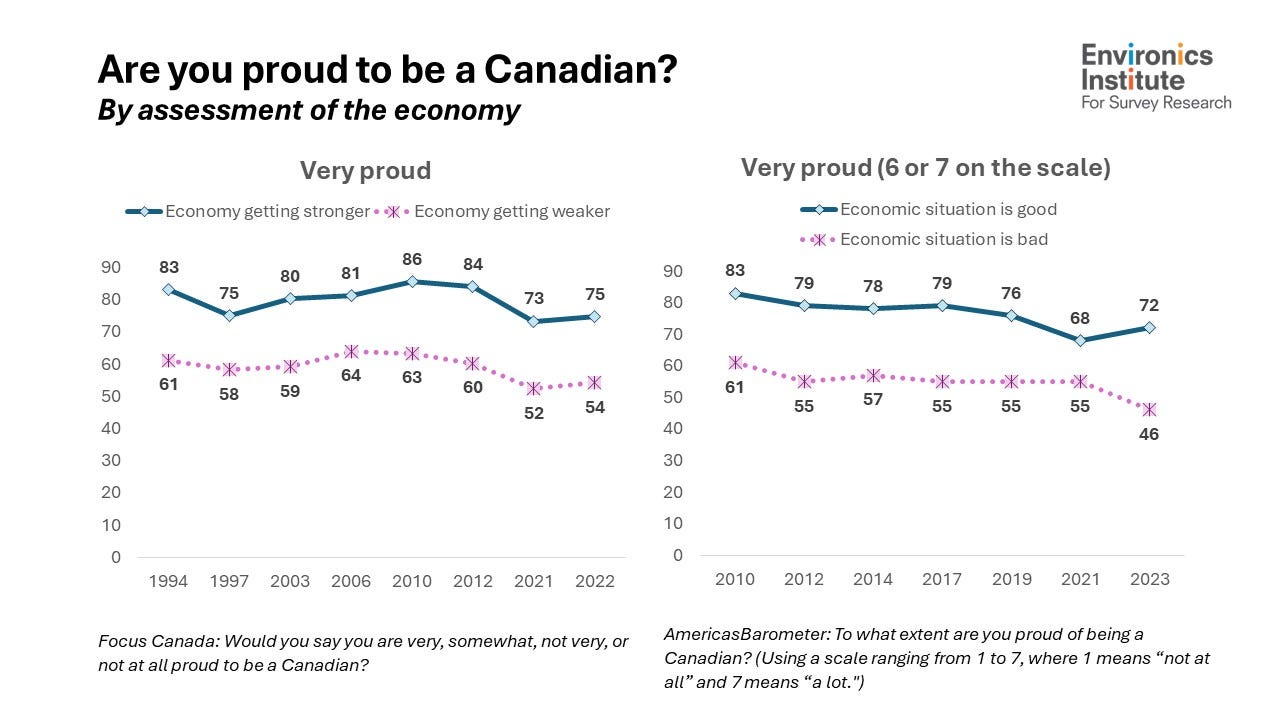

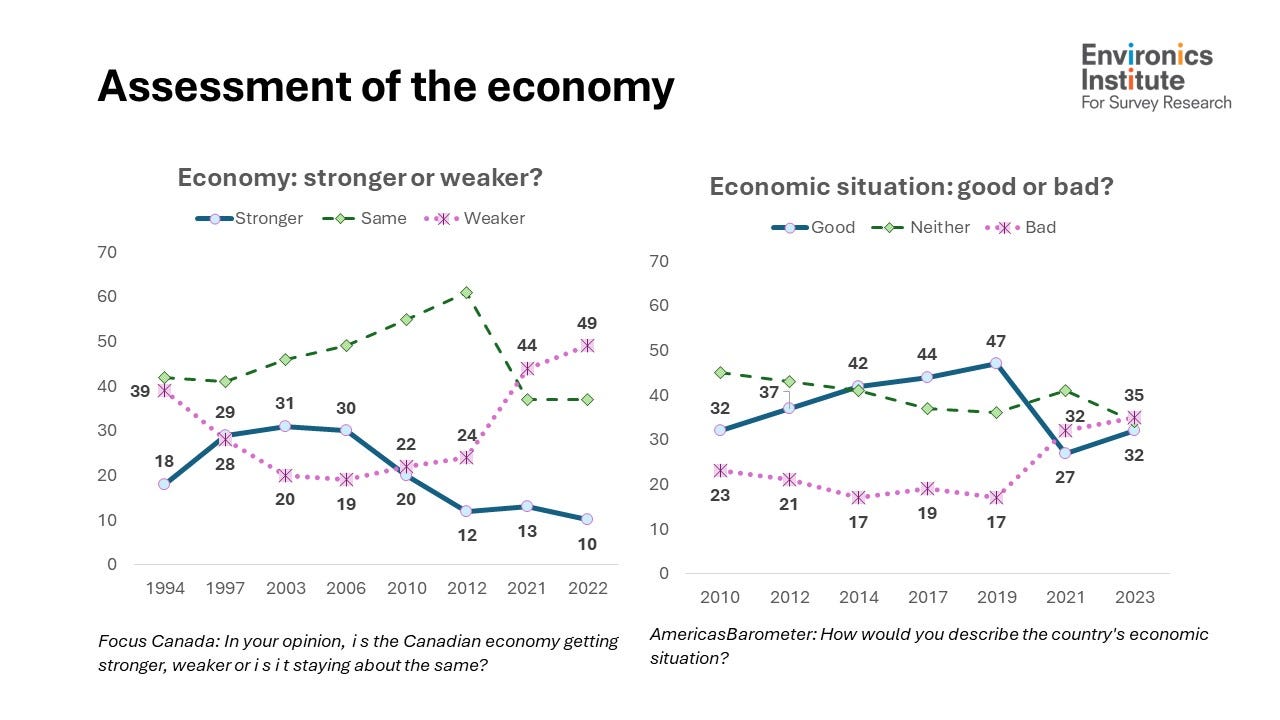

Next, let’s look at the relationship between feelings of national pride and economic outlook. This is worth considering, since we saw in an earlier newsletter that there’s a connection between the souring economic mood in recent years and lower satisfaction with Canadian democracy.

Clearly, there’s a connection between the two views: those who think the economy is doing badly are consistently much less likely (compared to those who think the economy is in good shape) to say they are very proud to be a Canadian.

And what happened just prior to 2021, when the surveys started to show a drop in strong national pride? The proportions saying the economy is getting weaker, or that the country’s economic situation is bad, jumped up.

This would be a shorter edition of the newsletter if we left things at that, but there’s more fun to be had. Focusing solely on the worsening economic outlook still leaves open the question of whether national pride has fallen more among those on the political left, leaving a vacuum to be filled by those on the right. Luckily, one of our two surveys asks people where they place themselves on the left-right scale, which gives us this:

Those on the political left did experience a post-2015 election bump in strong feelings of national pride, which has since ebbed, but they end up close to where they were a decade ago. But among those on the right, pride has fallen steadily since 2012. There is currently no difference between those on the left and those on the right – in terms of the proportions saying they are very proud (keep this is mind, as I’ll come back to it next time, when I will compare Canada to the United States). But, if we take the averages of the three surveys either side of 2017, there has been no change among those on the left (an average of 64% for both periods), but a significant drop among those on the right (from an average of 80% to 64%).

To recap: the arrival of a Liberal government in Ottawa, with its alleged insistence on reminding Canadians of the country’s historical failings, was met by a drop in national pride among those on the political right, not the left – which is the opposite of the argument I quoted at the outset.

In Canada, however, ideological labels are not proxies for political parties (if you missed that discussion, you can catch up here). So, let’s have a look at the trend, based on party preference (note that the federal vote intention question isn’t always included in the second of the two surveys).

Strong feelings of national pride have held fairly steady among federal Liberal party supporters, not only over the last few years, but since 1985. This seems a little surprising if you hold the view that the current prime minister has really made “denigrating Canada central to his Liberalism.” But national pride has taken a big hit since the 2015 election among Conservative Party supporters (and, to some extent, among NDP supporters as well).

What’s interesting about the Focus Canada survey, which covers a longer time period, is that it shows that Liberal supporters’ feelings about the country don’t swing up and down that much depending on who’s in power. About four in five felt very proud of being a Canadian under the prime ministerships of Mulroney, Chrétien, Harper and Trudeau. But feelings of pride among Conservative Party supporters seem a little more contingent: they dipped by about 10 percentage points in the Chrétien period, recovered under Harper and have now dipped again by more than 20 points under Trudeau.

I’m not quite sure what to make of this, except to say that it casts doubt on the hypothesis that national pride has become more muted because some Canadians are getting too woke.

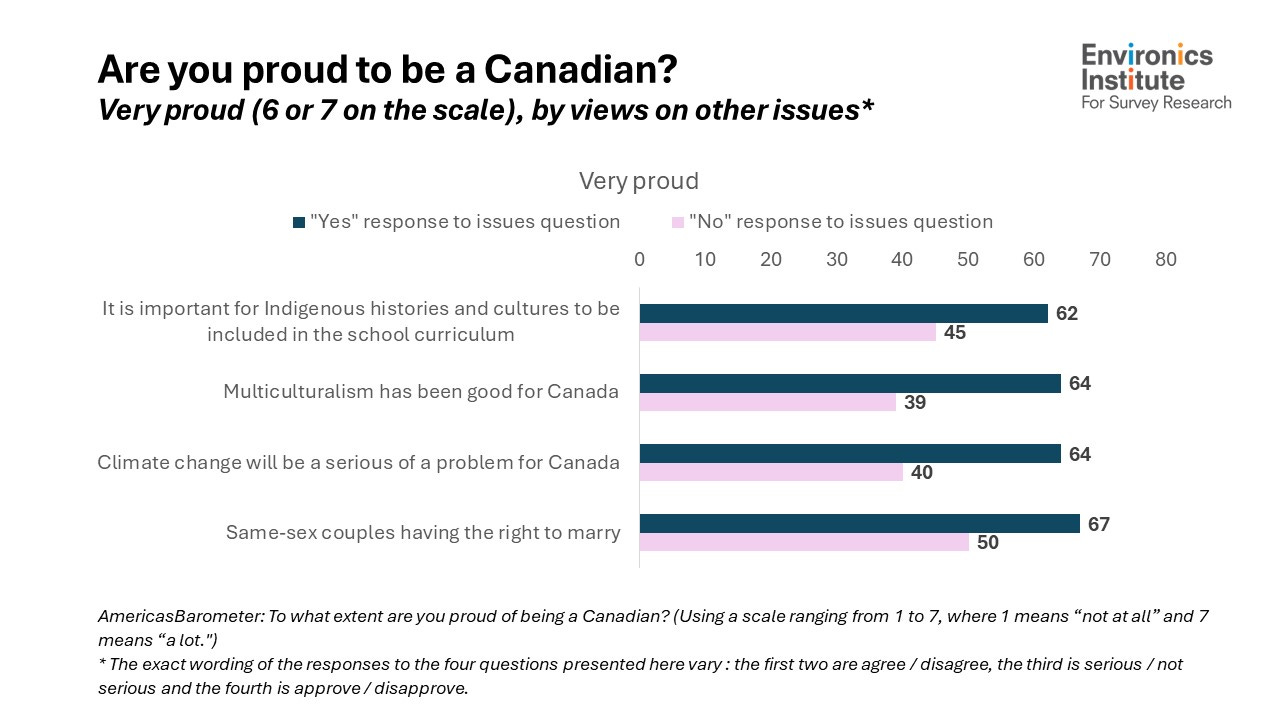

And if more evidence was needed, let’s look more directly at the relationship between feelings of national pride and opinions on other social issues. Both of our surveys show that those who are more concerned about social and racial equality are more likely to be very proud of being a Canadian. For instance, the 2022 Focus Canada survey finds that 63 percent of those who agree that “the government should do much more to make sure racial minorities are treated fairly” are very proud to be a Canadian, compared to 55 percent of those who disagree. Similarly, the 2023 AmericasBarometer survey finds that strong feelings of national pride are higher among those who are more supportive of multiculturalism, same-sex marriage and learning about the history of Indigenous Peoples, as well as those who are more worried about climate change.

I don’t find any of this that surprising. It’s only surprising if you assume that a concern with social and racial justice in Canada somehow leads people to feel less proud of their nationality.

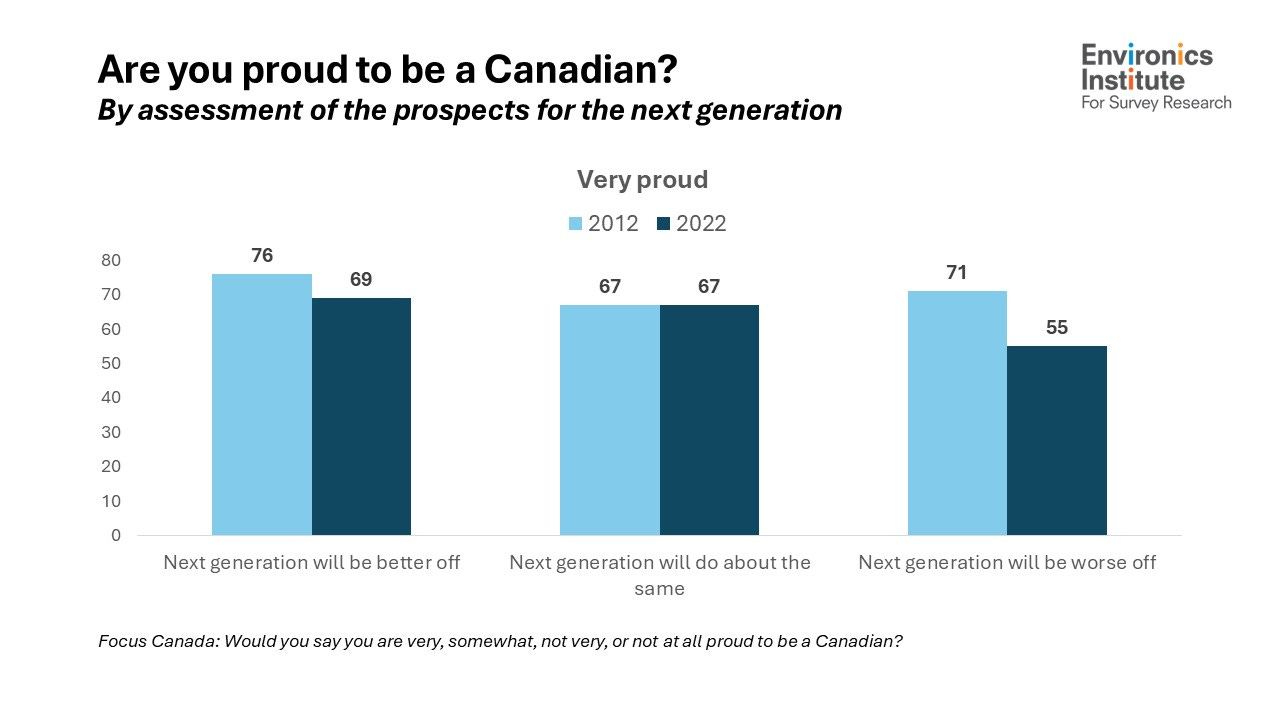

If you’re really determined to lay the blame for the recent decline in national pride at the feet of the current federal government or prime minister, there is a silver lining. Over the past decade, strong feelings of national pride have declined much more among those who think the next generation will be worse off.

In other words, you can point the finger at the Liberal Party of Canada if you really want to, but only if you shift the narrative from “Canada is too woken” to “Canada is too broken.”

But now we’ve started to go in circles. We’ve already seen that feelings of national pride correlate with views on the strength of economy and with party preference. And both of those in turn correlate with optimism or pessimism about prospects for the next generation. We’re just measuring the same thing in different ways.

It’s undeniable that many Canadians – especially opponents of the current government – are feeling disappointed, if not angry, about current economic conditions (including the cost of living, the affordability of housing and the ability of younger adults to get ahead). Relatedly, some are feeling less inclined to express their national pride as strongly as they might have done five or 10 years ago.

I don’t think it’s really much more complicated than that.

The data in this post are from the Environics Institute’s Focus Canada and AmericasBarometer surveys; details of the methodology of all our surveys are available on the Projects section of our website.

What is the Environics Institute for Survey Research? Find out by clicking here.

Follow us on other platforms:

· Twitter: @Environics_Inst or @parkinac

· Instagram and Threads: environics.institute

Some very interesting stuff. I do wonder about the impacts of “Canada is Broken” as a theme song.

Another thing I wonder is, what exactly does it mean to be “proud” to be Canadian? For most of us, it was dumb luck to be born here.

Some more meaningful questions to track might include “how fortunate do you feel to be a Canadian?” Or questions about our individual commitment or connection to the country. It would also be wonderful to dig into some of the insightful questions raised in this piece to gauge, and track over time, the impacts of greater awareness of indigenous maltreatment and efforts at true reconciliation. And relate those trends to national pride.