When we talk about regionalism in Canada, we focus inevitably on “the West.” We explore “Western alienation,” consider whether “the West wants in” and even contemplate “Wexit.”

No one would ever pretend that the region is monolithic. But there is a sense that Manitobans, Saskatchewanians, Albertans and British Columbians have enough historical and present grievances in common that we can speak of a shared regional, Western Canadian perspective about the country and how it works.

I’m becoming less convinced of this, however, based on the survey data I see. Saskatchewan and Alberta are certainly closely aligned – check out this report to see how they stick together and stand out compared to all the other provinces on different measures of regional discontent. But opinions in these two provinces are not always echoed in Manitoba or (especially) B.C.

Just how different are Saskatchewan and Alberta from their two Western neighbours? The best way to illustrate this is to return to the identity question I wrote about last time. As a reminder, here is the question we ask:

People have different ways of defining themselves. Do you consider yourself to be …?

A Canadian only

A Canadian first, but also as someone from your province

Equally a Canadian and someone from your province

Someone from your province first, but also a Canadian

Someone from your province only

In the survey, the words “someone from your province” are replaced with the appropriate term for residents of each province, for instance, an Albertan, a Quebecer or a Nova Scotian.

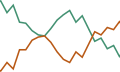

Let’s be honest and confess that Canadian political scientists first started to use this question to study identity in Quebec. And it’s easy to understand why. Here’s the proportion identifying as someone from their province first, or someone from their province only, in Quebec and Ontario, broken down by provincial vote intention.

Two things are blindingly obvious: first, that the provincial identity is much stronger overall in Quebec than in Ontario; and second, that identity is politicized in Quebec (but not in Ontario) in the sense that it differentiates the supporters of various provincial political parties from one another.

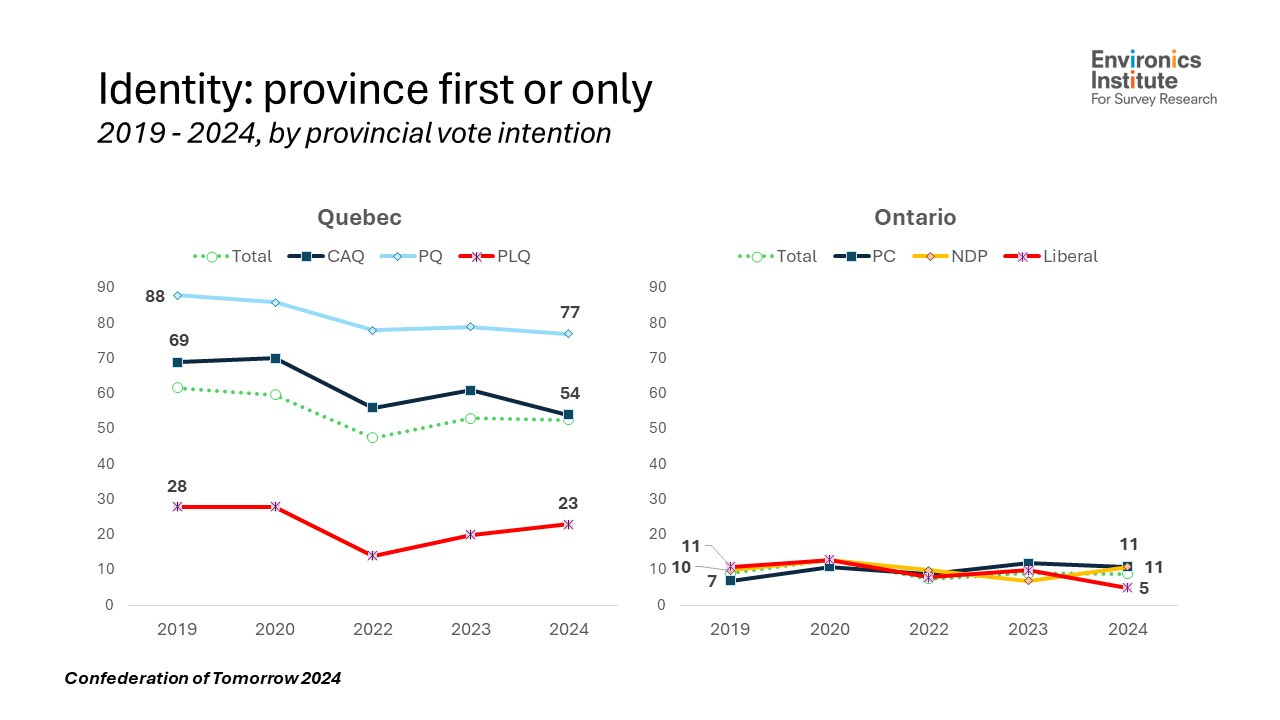

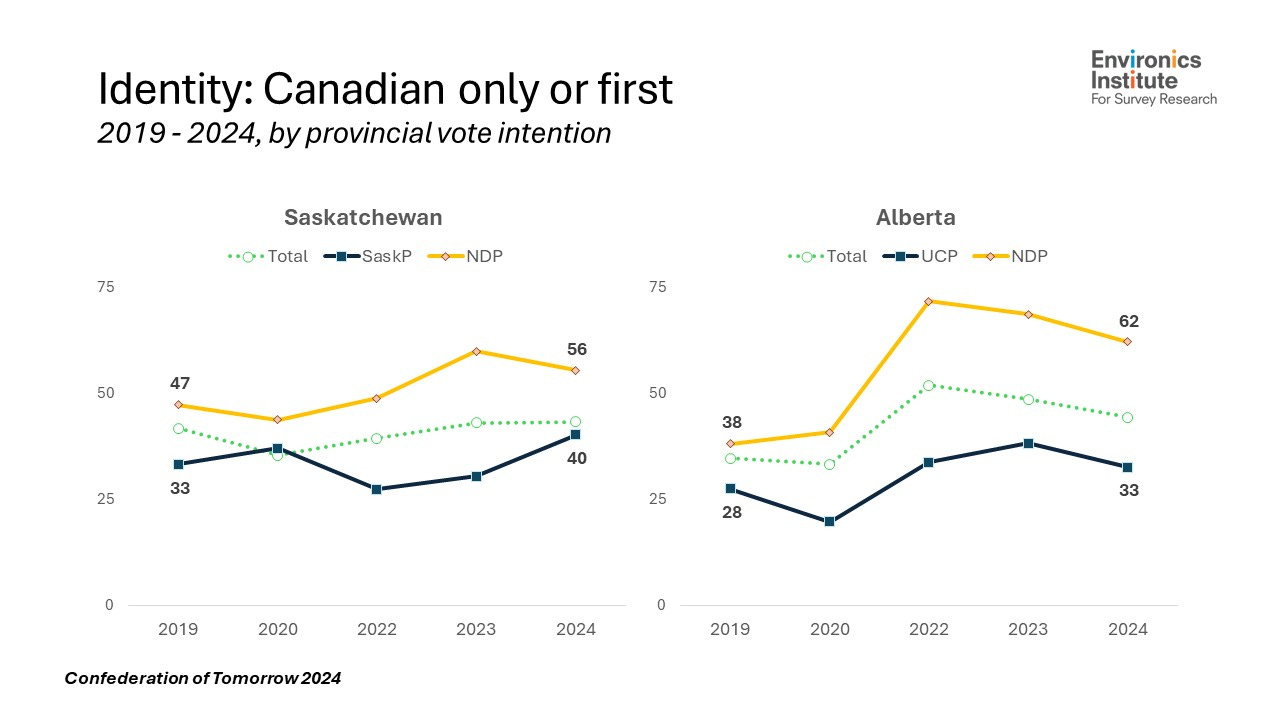

So far, so good. I wonder what Saskatchewan and Alberta look like? This time, I’ll show the figures for both “Canadian only or first” and “province first or only” (I’m leaving out “both equally”).

Provincial identities may not overshadow the Canadian identity in Saskatchewan and Alberta to the same extent as in Quebec, but the pattern nonetheless resembles that of Quebec more so than that of Ontario – particularly in the extent to which identity in these two Western provinces is politicized. Supporters of the provincial NDP and the provincial conservative parties in Saskatchewan and Alberta likely differ on a range of policy issues such as climate change and health care; but, like Quebecers, they also differ on the balance of national and provincial identities.

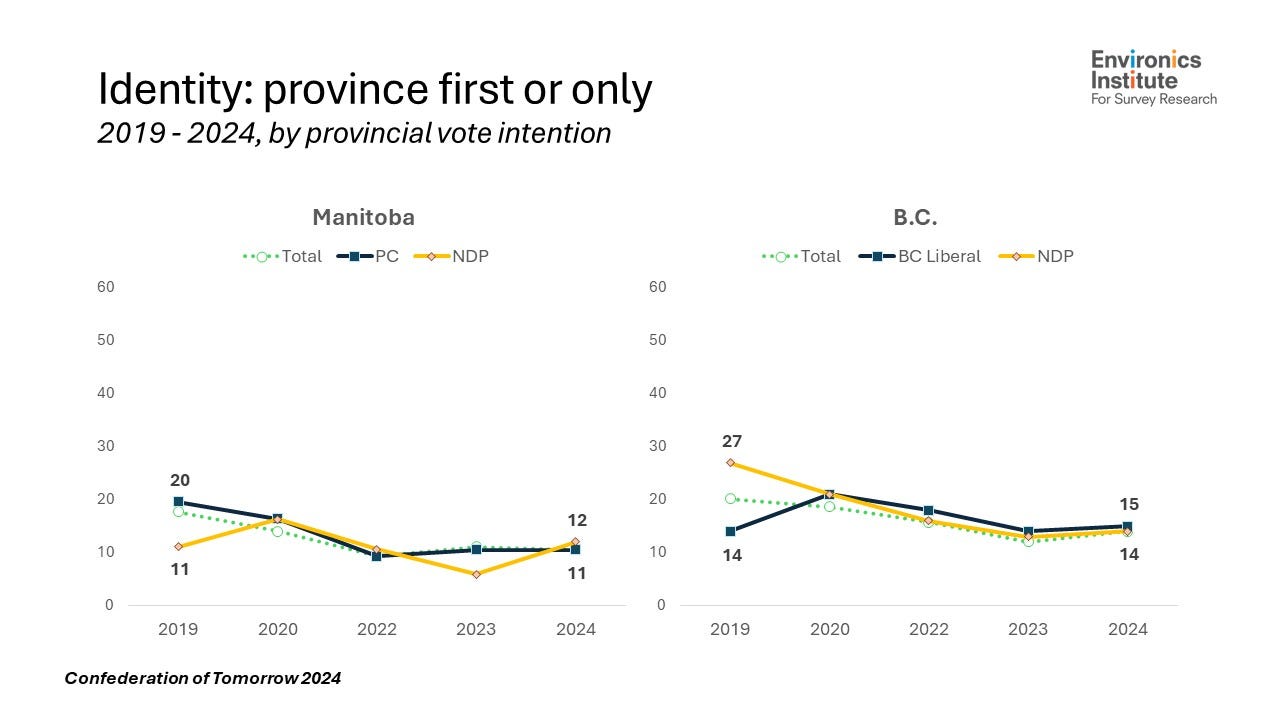

Meanwhile, in Manitoba and British Columbia…

I don’t want to insult anyone here, but these provinces look more like Ontario than their Western Canadian neighbours. The pull of the provincial identity is not particularly strong, nor does identity differentiate groups of provincial partisans from one another (things would not look much different if we added in B.C. Conservatives in 2024).

(By the way, I’m showing the data across all the available survey years, not because I’m trying to make a point about changes over time, but because I’m trying to show that the patterns are consistent enough that we can be confident in our conclusions. The sample sizes for some provincial parties in some years can get fairly small; for this reason, we shouldn’t make too much of small changes from year to year. It’s the overall patterns over several years that matter.)

This exercise leads me to two conclusions.

The first is to question how useful the term “Western alienation” is these days when describing political dynamics within the federation. Attitudes and identities in Saskatchewan and Alberta are unique – they differ not only from other provinces in Central and Eastern Canada, but from the other two Western provinces as well. We need a new term to capture the political orientation that characterizes these two provinces, but not “the West” (or even the Prairies) as a whole.

The second is to advance the claim that the country is divided, not so much between West and East, but into two other groupings of provinces: those where identity (understood in this particular federal-provincial context) infuses the contest between provincial parties (Quebec, Saskatchewan and Alberta), and those where it doesn’t (Ontario, Manitoba and B.C.).* This may a more useful lens to use when discussing the politics of federalism (and regional alienation) in Canada.

* I’m all too aware that Atlantic Canada is missing in this analysis. In any given year, the provincial samples in that region are too small to allow for breakdowns by provincial vote intention. The solution is to merge the surveys across years, but that’s a project for another day.

This post features data from the 2024 Confederation of Tomorrow Survey of Canadians. The author is solely responsible for any errors in presentation or interpretation.

The Confederation of Tomorrow surveys give voice to Canadians about the major issues shaping the future of the federation and their political communities. They are conducted annually by an association of the country’s leading public policy and socioeconomic research organizations: the Environics Institute for Survey Research, the Centre of Excellence on the Canadian Federation, the Canada West Foundation, the Centre D’Analyse Politique – Constitution et Fédéralisme, the Brian Mulroney Institute of Government and the First Nations Financial Management Board.

The 2024 study consists of a survey of 6,036 adults, conducted between January 13 and April 13, 2024 (82% of the responses were collected between January 17 and February 1); 94% of the responses were collected online. The remaining responses were collected by telephone from respondents living in the North or on First Nations reserves.

The western provinces are not monolithic. Edmonton does not follow the mold of “alienated Alberta”. Calgary is behaving more and more like a large urban centre (liberal). In BC, the interior is more like Alberta in their political leanings but they are buried by the large urban population of Vancouver area. The idea of western alienation is nonsense. A more useful descriptor would be urban vs rural. Rural regions are economically tied to the land. The economies of these areas are dominated by agriculture, resource extraction (fossil fuels as well as mining.) Their politics are conservative. When you divide the nation up on rural vs urban, Western Ontario, the farm belt of the Great Lakes lowlands, the farmlands of Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan line up well with the hinterlands of BC.

The fossil fuel industry owns the public discourse space in Alberchewan in a way that is unique to those provinces.