Barriers to immigrants’ employment

Do employers recognize foreign experience, qualifications and credentials?

Canada seeks to attract immigrants who are highly skilled or well-educated. But it’s often difficult for immigrants to find jobs that make use of their skills, particularly when employers don’t recognize the work experience or qualifications they earned before moving to Canada.

This problem has several dimensions. In some cases, employers are simply biased against foreign compared to Canadian experience or training.1 In other cases, employers may have difficulty understanding what foreign-earned credentials mean (what are they equivalent to in Canadian terms?). And, in other cases still, immigrants may be shut out of the jobs they trained for because they lack the right piece of paper from a professional association in Canada.2

To gauge the scale of this problem, the Survey on Employment and Skills asked immigrants about their experiences in the Canadian labour market. Specifically, we asked whether each of the following has been a major barrier to their progress at work in Canada, a moderate barrier, a minor barrier or not a barrier at all:

Employers not valuing the work experience you had in another country before you moved to Canada.

Employers not recognizing the professional qualification you earned in another country before you moved to Canada.

Employers not recognizing the educational credential (for example, a diploma or a degree) that you earned in another country before your moved to Canada.

And here’s what we found:

About one in four immigrants say that each of these is has been a major barrier to their progress at work in Canada, and just over two in five say each has been either a major or a moderate barrier.

The question was asked of all immigrants, regardless of whether they’re in the labour force or not (as it’s possible that some who encountered these barriers may have left the labour force as a result). The option of saying that the question “does not apply” was included, both because some people may choose not to work (and so could not speak to barriers to their careers); and because some immigrants may not have any foreign experience, qualifications or credentials (for instance, if they arrived in Canada as a child).

When we look at the results only for those currently in the labour force (meaning that they’re either employed or looking for work), then slightly higher proportions report that employers not recognizing their experience, qualifications or credentials has been a barrier to them at work. Between 46 and 48 percent say that each of these has been either a major or a moderate barrier.

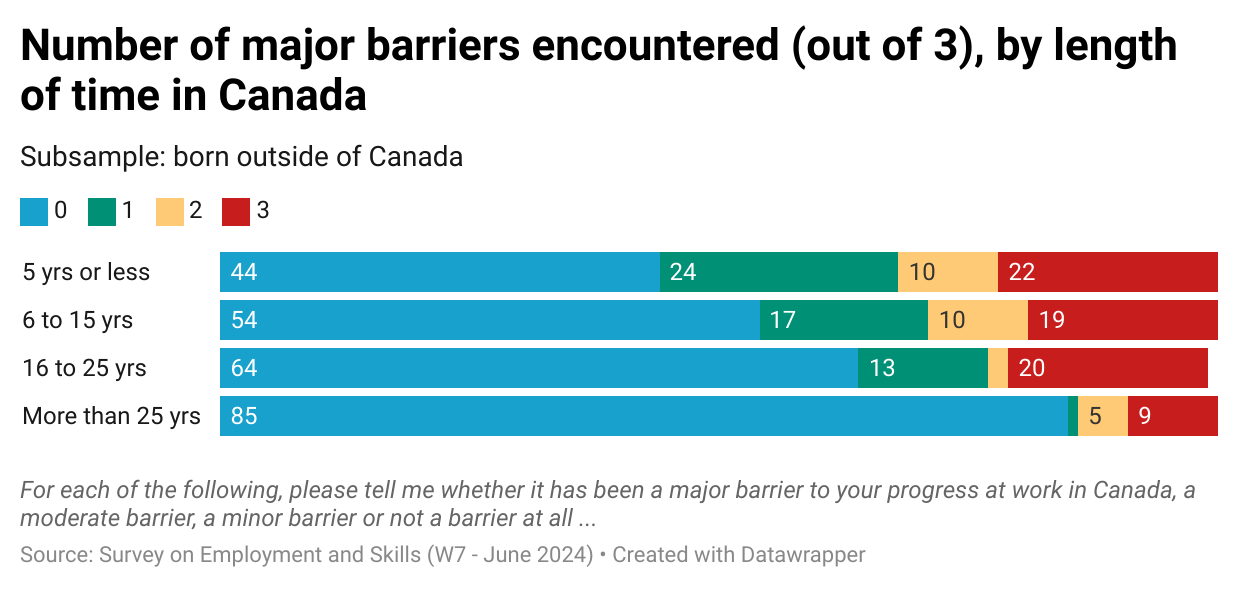

Another way to illustrate the challenges faced by immigrants is to count how many of the three items mentioned – lack of recognition of work experience, professional qualifications and educational credentials – are encountered as major barriers: some may face none, while others may come up against all three. Overall, 16 percent of immigrants report that all three of these were major barriers, while seven percent report two, 13 percent report one and 64 percent report none.

Recent and racialized immigrants

Not all immigrants are equally likely to encounter these barriers. There’s significant variation in experiences based on two factors: length of time in Canada and racial identity.3

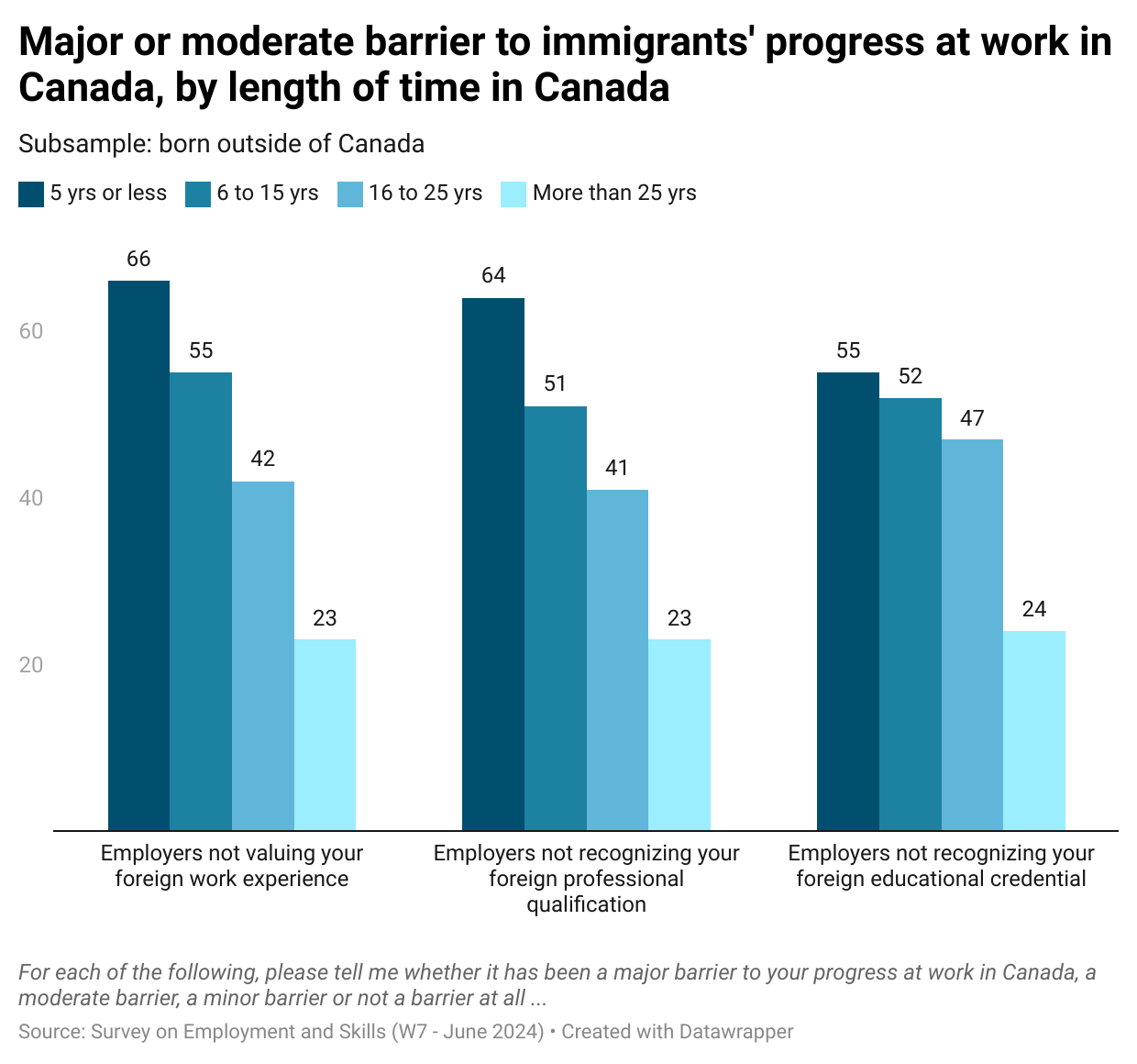

It’s not surprising that recent immigrants – those who have been in Canada for no more than five years – are the most likely to say that lack of recognition of their foreign experience, qualifications or credentials is a major or moderate barrier to their progress at work. But it’s notable that this is also reported by more than one in two of those who have been in Canada longer (between 6 and 15 years), and by more than two in five of those who have been in Canada for between 16 and 25 years.

We can’t tell from the survey whether immigrants who have been in Canada for many years are reflecting on recent experiences or recalling the barriers they encountered soon after they first arrived. We can simply make two observations: that recent immigrants are the most likely to be affected; and that a significant proportion (over 40%) of immigrants who have been in Canada longer also mention encountering this type of barrier to their progress at work.

In addition, racialized immigrants are much more likely to encounter these barriers than are immigrants who are white.4 Immigrants who identify as South Asian are especially likely to have experienced lack of recognition of their foreign experience, qualifications or credentials as a major or moderate barrier to their progress at work.

As the next two charts show, the proportions of immigrants saying that one or more of these were major barriers impeding their progress at work are much higher among both of these groups – that is, for immigrants who arrived in Canada more recently and those who are racialized (again, particularly those who identify as South Asian, although immigrants who identify as Black are the most likely to have encountered all three barriers.)

Impact of barriers

As we’re working with survey data, we can’t say much definitively about how these barriers have affected immigrants’ success in the labour market since their arrival in Canada (we don’t have access to detailed employment and earnings histories, for instance). But we have some clues. Job satisfaction is lower among immigrants who have encountered at least one of the three as major barriers, compared to those for whom none of them were major obstacles. And those who have encountered at least one of the three as major barriers are more likely to be worried about themselves or a member of their immediate family finding or keeping a stable, full-time job; and are more likely to describe their income as being insufficient.

Immigrants make up a significant portion of Canada’s labour force. Making poor use of their education, training and skills is a loss both for the individuals affected and for the country’s overall prosperity. Governments, employers and advocacy groups are aware that this lack of recognition of experience, qualifications and credentials is a problem. These survey findings can reinforce this awareness by moving beyond anecdotal evidence and documenting the extent of the problem from the immigrant perspective, based on their experiences seeking employment in Canada. As we’ve seen, the lack of recognition of foreign experience, qualifications or credentials poses a barrier to employment – to at least a moderate extent – for more than two in five immigrants in the labour force. Surveys, such as the Survey on Employment and Skills, should return to this topic in the future to assess whether any progress in addressing this issue is being made.

The data in this post are from the Survey on Employment and Skills. This survey is conducted by the Environics Institute for Survey Research, in partnership with the Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University and the Future Skills Centre. The 7th wave of the study consists of a survey of 5,855 Canadians age 18 and over, conducted between May 30 and July 4, 2024, in all provinces and territories. It was conducted both online (in the provinces) and by telephone (in the territories). More information about the survey is available on the Environics Institute website. The author is solely responsible for any errors of presentation or interpretation.

The Survey on Employment and Skills is funded primarily by the Government of Canada’s Future Skills Centre / Le sondage sur l’emploi et les compétences est financé principalement par le Centre des Compétences futures du gouvernement du Canada.

What is the Environics Institute for Survey Research? Find out by clicking here.

Follow us on other platforms:

Bluesky: @parkinac.bsky.social

Twitter: @Environics_Inst or @parkinac

Instagram and Threads: environics.institute

This may be bias in the sense of favouring what you know best; or, in some cases, it may amount to discrimination against people from different cultures or countries.

For an example of the problem as it affects immigrants in the health care sector, see the materials published by SRDC in connection with this project: The Labour Market Integration of Internationally Educated Health Professionals.

Answers do not vary significantly by gender. Older immigrants (age 55 and older) are less likely to have encountered each of these barriers, but this may be a reflection of length of time in Canada (most older immigrants have been in Canada for 25 years or longer). Older immigrants are also less likely to be in the labour force.

In this survey, racialized respondents are those who are not Indigenous and who select any racial or cultural category other than “white” as the one that best describes them (the categories presented are the same as the ones used in the census).

Thanks for an interesting analysis of a critical and longstanding issue.

I doubt your data can help pull out this issue but I wonder about bias based on country of origin and the perception of its reliability. Many years ago when on posting in Australia I met with a Canadian researcher who was looking for a means of meshing qualification tests for doctors. It seemed clear that across Australia, NZ, UK and Canada that there was about an 80% overlap in the subject matter of testing for new doctors. The thought was that if the three countries could bump that number up a bit then there would be an easy step to quick recognition of the qualifications of anyone passing the test in any of the countries.

Of course, an underlying assumption was that the quality of medical education in each country was at a level of reliability that a graduate passing the test could be assumed to be good enough to work in any of the four countries. I wonder though if a similar assumption would hold among the Colleges of Physicians in Canada for graduates of medical school in Pakistan, India, Cuba, and so on. Would something similar apply to engineers or other professions.

Moreover, it might be instructive to determine whether qualifications from the same country might be see differently depending on the racial identity of the graduate. Would racialized doctors from South Africa or the UK feel greater barriers exist from their while immigrant counterparts?