National pride in Canada once appeared as something we could take for granted. In 1985, when Environics first began asking Canadians if they were proud to be a Canadian, the proportion saying they were at least somewhat proud was close to 100 percent. Even in Quebec, most expressed some pride in being Canadian, and only a handful said they were not very or not at all proud.

Over the ensuing three decades – until the mid-2010s – roughly seven in ten people in the country consistently said they were very proud to be a Canadian; more than nine in ten said they were either very or somewhat proud. Since then, however, the strength of national pride has weakened considerably. This newsletter documents this dramatic shift and explores what may lie behind it.

The results presented here update the Environics Institute’s previous reports on this topic. The results up until 2022 were first published in the report on The Evolution of the Canadian Identity. These results were analyzed in more detail in a newsletter in 2024 on the decline of national pride in Canada. The analysis that follows now includes the latest survey results, from September 2024.

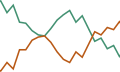

Proud to be a Canadian: 1985 to 2024

In a series of national public opinion surveys conducted between 1985 and 2016, the proportion saying they were very proud to be a Canadian hardly changed, standing at a little above 70 percent. But this proportion then fell sharply, by 20 percentage points, from 73 percent in 2016 to 53 percent in 2024.

Over the same period, the proportion saying they are somewhat proud to be a Canadian increased, from 19 percent to 29 percent. As a result, while the proportion feeling very proud declined by 20 points, the proportion saying they are either very or somewhat proud fell by a lesser amount – by 11 points – from 93 percent to 82 percent.

The proportion saying they are not very or not at all proud, or choosing not to express an opinion, have both increased. In 2024, 12 percent say there are either not very or not at all proud to be a Canadian, up from four percent in 2016.1 The proportion that doesn’t express a clear opinion increased from three percent in 2016 to six percent in 2024.2

To sum up: the vast majority of Canadians (more than four in five) remain at least somewhat proud of their nationality. But, over the past decade, the strength of national pride in Canada has become more muted: fewer feel very proud, but more feel somewhat proud. While relatively few say they don’t feel proud to be a Canadian, this proportion has increased nonetheless, from about one in 20 to closer to one in 10.

Regional trends

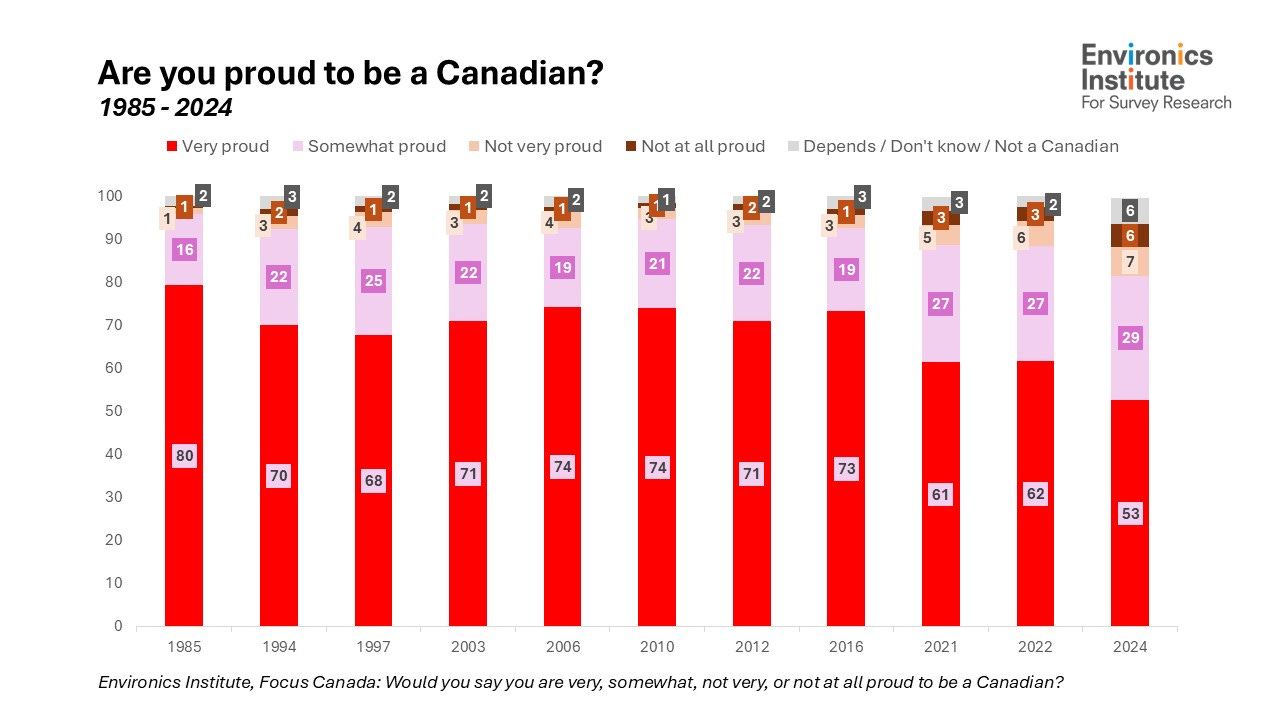

To help make sense of this trend, we can look at how pride in being Canadian varies among different population groups – starting with differences by region. The key point here is that the overall decline in national pride is not driven by changes in opinion in Quebec.

The proportion of Quebecers who say they are very proud of being Canadian has always been much lower than in the rest of the country. This proportion has also declined in the past decade, following the national trend. But it has declined much more sharply outside of the province. As a result, the gap between Quebec and the rest of the country is now much narrower than it was during the three decades between the mid-1990s and the mid-2010s.

And, while the extent to which Quebecers feel proud of being Canadian has cycled up and down over the past 40 years, the drop in the rest of the country is clearly without precedent.

Outside of Quebec, the regional trends are similar. Since 2012, the proportion saying they are very proud to be a Canadian has fallen most in Alberta (down 33 percent points) and least in Atlantic Canada (down 18 points) – but what matters more is that the decline has been significant in each region.3

Age groups

The extent of national pride has been strongest among older Canadians, and less so among younger cohorts. But, up until 2022, it did not appear that the decline in national pride was any more pronounced among younger generations.

Things look a bit different with the addition of the 2024 results: the proportion of Canadians age 18 to 29 who say they are very proud of being a Canadian fell sharply (by 25 percentage points) between 2022 and 2024.

As a result, the updated picture over the longer term is as follows: between 2012 and 2024, the proportion that is very proud fell by 14 points for those age 60 and older, by 16 points for those age 45 to 59, by 28 points for those age 30 to 44, and by 27 points for those age 18 to 29.

While the decline in national pride now appears to be more pronounced for younger compared to older Canadians, it’s important to note that:

a significant decline has occurred since 2012 among all age groups;

the greatest decline has occurred not just among those in the youngest age group, but by those in the younger two groups (18 to 29, and 30 to 44) – suggesting it’s not a development exclusive to “youth”;

the drop in the proportion of those age 18 to 29 who say they are very proud of being a Canadian was accompanied by an increase in the proportion who say they are somewhat proud or who do not express an opinion either way.4 The proportion of younger Canadians saying they are not very or not at all proud increased by a much smaller amount (up 3 points since 2012, from 9% to 12%) and remains relatively modest.

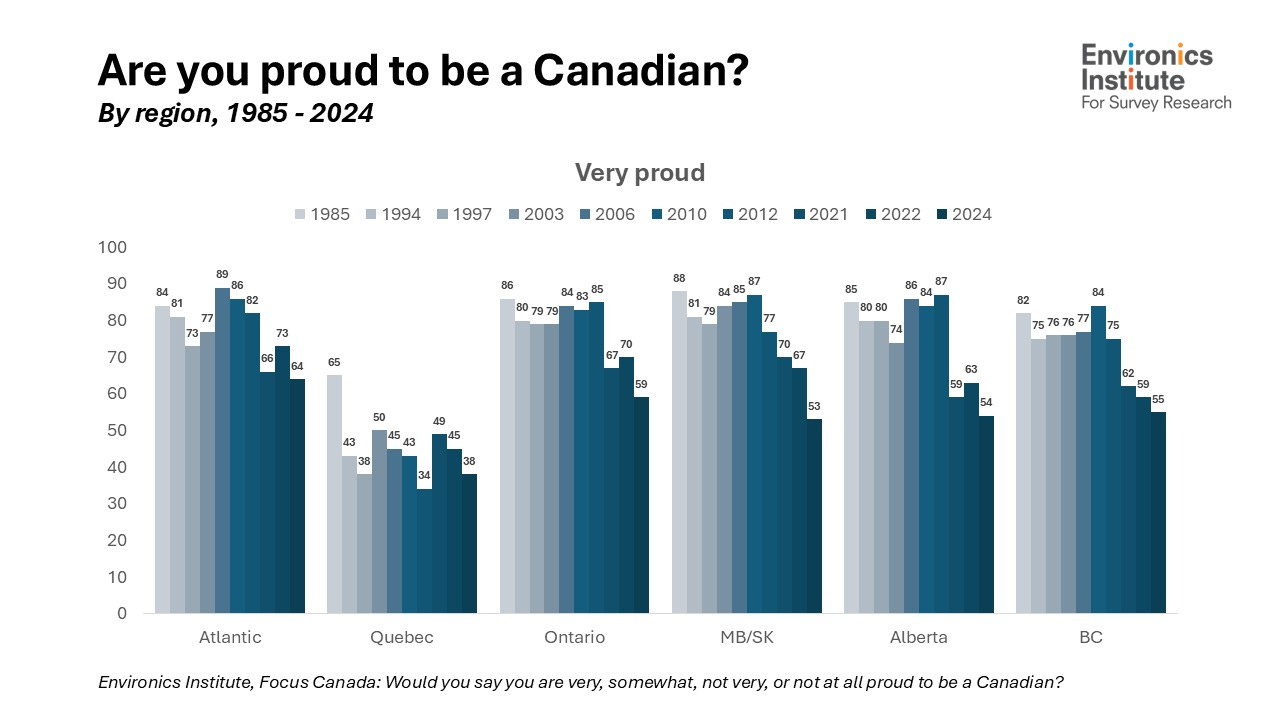

Federal party support

For the first two decades in the period covered by our surveys – from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s – there was little difference in the extent to which supporters of the three main federal political parties felt very proud of being a Canadian. This has changed: today, feelings of national pride differ considerably, particularly between Liberal and Conservative Party supporters. Strikingly, the extent of strong national pride among Conservative Party supporters is now closer to that expressed by Bloc Québécois supporters than it is to that expressed by their Liberal Party rivals.

Here is a summary of the trends:

Supporters of the federal Liberal Party are currently the most likely to say they are very proud of being a Canadian (72%). And, while the proportion of Liberal Party supporters expressing this opinion is lower today than in 2012, it has dropped by only nine percentage points.5

By contrast, supporters of the Conservative Party are currently much less likely to say they are very proud (46%). Moreover, the proportion of Conservative supporters expressing this opinion has dropped dramatically since 2012, by 36 points. Over that period, the proportion of Conservative Party supporters who are not very or not at all proud has risen from one percent to 17 percent.

NDP supporters (61%) are currently more likely than Conservative Party supporters, but less likely than Liberal Party supporters, to say they are very proud of being a Canadian. But, while the proportion of NDP supporters who say they are very proud is lower than it was in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, it is not lower than in 2012 – and, in fact, has risen slightly over the past three years, in contrast to the trend for other partisan groups. Only six percent of NDP supporters are not very or not at all proud.

Finally, supporters of the Bloc Québécois are, not surprisingly, much less likely to say they are very proud of being a Canadian; but, in this case, there is no steady downward trend. In fact, the proportion of this party’s supporters that is very proud is currently twice as large as it was in 2012.

Direction of the economy

The strength of feelings of national pride has always been related to economic outlook: those saying that the Canadian economy is getting stronger are more likely to say they are very proud of being a Canadian, compared to those who say the economy is getting weaker or staying about the same.

The important implication of this pattern is that the changing economic mood also matters.

Since 2012, the proportion saying they are very proud of being a Canadian has declined across the board, though less so among those feeling optimistic about the economy: it has dropped by seven points among those who say the economy is getting stronger, by 14 points among those who say the economy is staying the same, and by 16 points among those who say the economy is getting weaker.

What’s just as important, however, is that during this period, economic pessimism grew significantly: the proportion expecting the economy to stay about the same dropped by 30 percentage points (from 61% to 31%) while the proportion expecting it to get weaker jumped by the same amount (from 24% to 54%). Thus, not only are those who expect the economy to get weaker less likely to feel very proud to be a Canadian, but there are many more people in this more pessimistic group today than there was a decade or so ago.

We should not be surprised, then, that a decline in economic optimism is accompanied by a dampening of strong feelings of national pride.

Attitudes to diversity

One explanation for the decline in national pride that continues to circulate points to an alleged excess of contrition over past injustices. Apparently, the problem stems from the sentiment, allegedly promoted in particular by the Liberal federal government, that “to be proud to be Canadian is to somehow fail to properly recognize the hurt this country has inflicted, and continues to inflict, on marginalized groups.” (This argument is also discussed in my previous newsletter on this topic.)6

The evidence, however, points in the opposite direction, as Canadians who express the most support for multiculturalism and ethnic diversity are more, not less, likely to say they are very proud of being a Canadian.

For instance, 56 percent of those who agree that “multiculturalism has contributed positively to the Canadian identity” say they are very proud of being a Canadian, compared to 37 percent who disagree with that statement. Similarly, 56 percent of those who agree that “the government should do much more to make sure racial minorities are treated fairly” say they are very proud, compared to 44 percent who disagree.

Key factors related to the decline in national pride

No single factor on its own accounts for the decline in the strength of feelings of national pride in Canada over the past decade.

Views about the economy, and political party preference, both matter – and they are not mere echoes of one another (which means that it’s not simply the case that it’s only Conservative Party supporters who have become more economically pessimistic, so that once you account for partisanship, the effect of economic outlook disappears – or vice versa).

The effect of economic outlook is fairly easy to explain: those who are more pessimistic about the economy are less likely to feel very proud to be a Canadian, and there are many more economic pessimists today than there were in earlier periods.

The effect of partisanship, however, has shifted. In 2012, there was little difference in feelings of national pride between Liberal Party and Conservative Party supporters; what mattered was whether one supported the Bloc Québécois or, to a much lesser extent, the NDP. But, in 2024, being a Conservative Party now matters a lot – as these partisans have become increasingly less likely to say there are very proud (and even, to a certain extent, at least somewhat proud) of being a Canadian.

In other words, the decline in national pride can be explained in terms of both growing economic pessimism, and a widening partisan gap on feelings of national pride between those who support the federal Liberal government (among whom feelings of pride remain fairly strong) and those who support the Conservative official opposition (among whom feelings of national pride have weakened considerably).

The remaining factor is that of age: younger Canadians have traditionally been less likely to express strong feelings of national pride, but this age effect has become more important in recent years. Again, it’s important on its own and not just as an echo of other factors (in other words, it’s not simply that younger Canadians have grown more economically pessimistic, or shifted support to the Conservative Party, because the effect of age remains even once these other attitudes are accounted for). But it’s worth emphasizing again that, in the case of younger Canadians (those age 18 to 29), the shift is mainly from feeling very proud to feeling somewhat proud, as the proportion in this age group feeling not very or not at all proud has increased by only three percentage points since 2012.

What remains unclear is whether we can expect the strength of national pride in Canada to continue to move in line with economic and political cycles – so that it rebounds once the economy improves or following a change of government – or whether the recent decline will prove to be more enduring. The evidence presented here about the relationship between pride, economic outlook and partisanship suggests that a rebound can be expected once the economic and political contexts shift, but only time will tell.

Thanks to Justin Savoie for contributing to the analysis and co-authoring this newsletter.

About the Survey

As part of its Focus Canada public opinion research program (launched in 1976), the Environics Institute updated its research on national pride in Canada. This survey was conducted in partnership with the Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University, and with the ongoing support of the Century Initiative.

The latest survey is based on telephone interviews conducted (via landline and cellphones) with 2,016 Canadians ages 18 plus between September 9 and 23, 2024. A sample of this size drawn from the population produces results accurate to within plus or minus 2.2 percentage points in 19 out of 20 samples. All results are presented as percentages, unless otherwise noted.

What is the Environics Institute for Survey Research? Find out by clicking here.

Follow us on other platforms:

Bluesky: @parkinac.bsky.social

Twitter: @Environics_Inst or @parkinac

Instagram and Threads: environics.institute

The total of combined categories may appear to add to more or less than the sum of the individual categories shown on the charts, due to rounding.

Those who don’t express a clear opinion includes those who say “it depends,” those who say they don’t know, and those who say they are not Canadian. Most of those who say they are not Canadian were born outside of the country; some may only be residents of Canada on a temporary basis.

Charts showing detailed breakdowns by region and age group exclude 2016 because the survey sample that year was smaller.

See note 2.

Charts showing detailed breakdowns by federal vote intention exclude 2016 because the vote intention question was not included in that survey.

In a variation of this argument, journalist John Ivison recently attributed the decline in national pride to the prime minister’s insistence that “that Canada has no core identity and is a “post-national” state.”

Interesting analysis and breakdowns. But I question whether the substitution from very to very or somewhat is something to be very concerned about. May just reflect a more realistic assessment of Canada and Canadian society, proud but with nuances. Partisan differences are very apparent so the "Canada is broken" rhetoric is likely having an impact.

Any sense whether this is a primarily Canadian phenomenon? Or has a similar trend been seen in other Western countries ?