Resilience, well-being and economic security

Another look at the interest of young adults in having children (with heat maps!)

How is young people’s sense of well-being affecting their plans for their future, including their interest in having children of their own?

This is the third part of our ongoing series exploring the factors that shape the extent to which young adults in Canada express an interest in becoming parents. Here’s where we left the story at the end of Part 2:

“Most younger adults in Canada either have children or say they would like to have children. But one in five say they would not like to have children. To understand why, it might be worth pausing before assuming that it must necessarily be related to the cost of living or of housing. Non-financial factors, including the sense of connection younger Canadians feel toward the communities they live in, and the opportunities they have for community engagement, seem worth exploring.”

You can revisit Parts 1 and 2 here:

Who wants to have children? Easing into the debate on declining fertility rates

Culture and community: a second look at who wants to have children

We’ve actually asked this question – “would you personally like to have children in the future?” – in three different surveys recently, which means we have the opportunity to corroborate our initial conclusions and explore the topic from several different angles. Here, we can make use of the breadth of information available in the second of these surveys – namely the Survey on Employment and Skills, conducted by the Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University, the Future Skills Centre, and the Environics Institute for Survey Research.

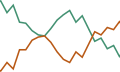

As with the previous survey, the starting point for our discussion is the finding that one in five adults under the age of 45 say they would not like to have children.1

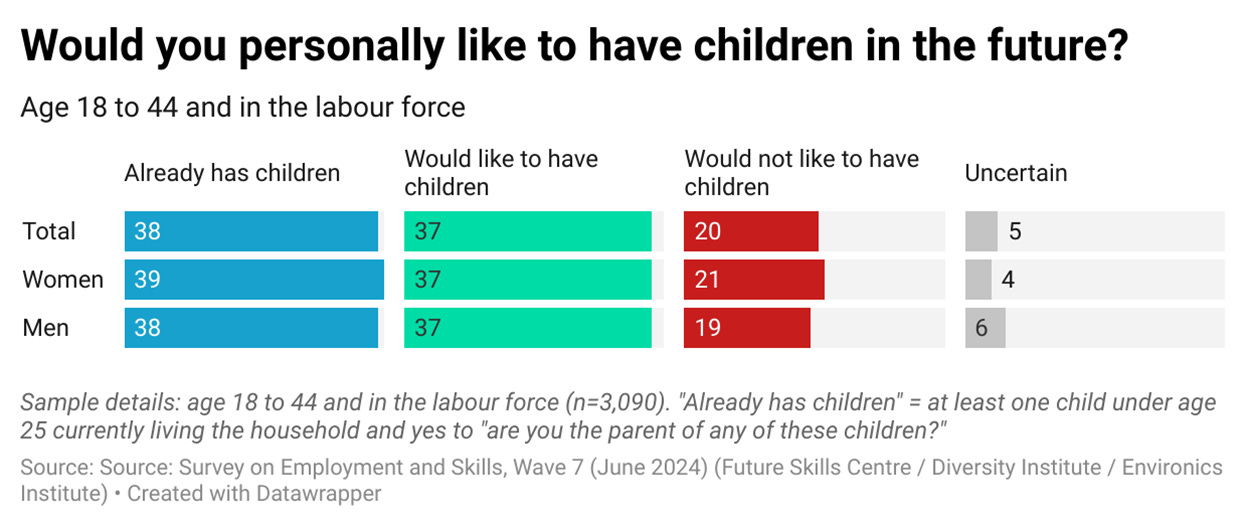

The next step is to look at which factors appear to be related to the intention to have children (or not). At first glance at least, financial factors seem to make at least some difference. For instance, among those most comfortable with their incomes, 18 percent say they would not like to have children; but this figure rises to 26 percent among those least comfortable.

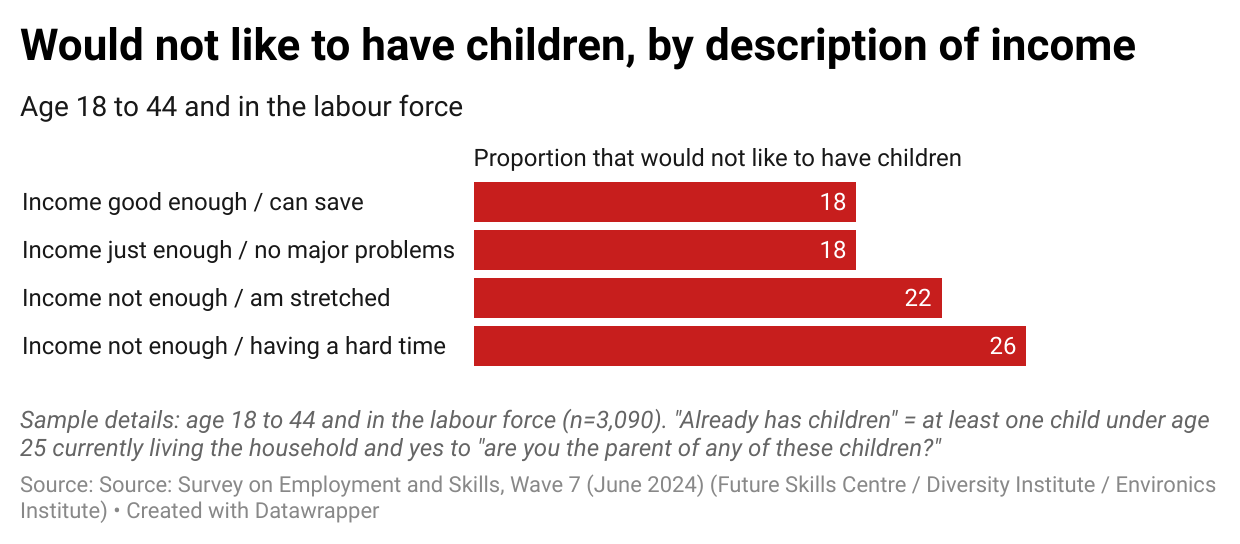

But once again, other “non-financial” factors appear to matter more. Those who say their mental health is only fair or poor are twice as likely to not want children, compared to those who rate their mental health as excellent or very good. There is a similar difference between those who always or often have a hopeful view of the future, and those who rarely or never do.

If you would like to see the details for the findings I just summarized, see the three charts in the appendix at the end of this article.

So far, so good – but we decided to push the analysis much deeper to make better sense of these various patterns. We did this in two steps.

First, we created three different indexes by combining the results of several related questions: an index of resilience, an index of well-being, and an index of economic security.2

Then we explored the relationship between each of these indexes (as well as other individual factors) and the desire to have children (or not), while controlling for socio-demographic factors such as age, gender, income and immigration status.3

The technique we used is called a “random forest model”. It works by combining the predictions of many simple models—called decision trees—to produce a more accurate and reliable result. This allows us to identify which factors are most strongly associated with the particular behavior we’re studying, without having to assume what those relationships look like in advance.4

This exercise confirmed that the resilience and well-being indexes have the most influence on the desire to have children (that’s what’s shown in the chart above). In other words, what is most strongly related to young adults’ interest in having children is, on the one hand, their outlook on the future and confidence in their ability to meet life’s challenges, and, on the other hand, their feelings of health and satisfaction. Although economic security is strongly linked to the desire to have children – more so in fact than any factor except resilience and well-being – its influence is notably weaker than that of resilience and well-being. And resilience and well-being are also much more relevant than other individual economic items, such as the sense of job security or the level of household income.

To illustrate this, it’s time to show off some cool new charts. These are “heat maps” constructed by this article’s co-author, Hubert Cadieux.

The first one shows how the resilience and well-being indexes interact. The probability of wanting to have children is lowest in the bottom left corner, when both resilience and well-being index scores are low. The probability of wanting to have children increases (i.e. the colours get darker) as you go up vertically (resilience increases) and as you go along to the right horizontally (well-being increases). And the probability of wanting to have children is highest in the top right corner, where both resilience and well-being index scores are high.

Still with us? Good. Now look at this second map which combines well-being with economic security.

Naturally, the probability of wanting to have children is still highest in the top right corner, where both well-being and economic security are high. But the probably remains low on the left-hand side of the box, where well-being is low, even as economic security rises (as you move straight up vertically from the bottom left corner). This tells us that increases in economic security cannot compensate for low well-being, when it comes to the desire to have children.

The same pattern emerges when we look at the interaction of resilience with economic security. Interest in having children remains low when resilience scores are low, even as economic security rises.

To be clear, the point is not that economic security is not important, nor that it has no impact at all on how young people feel about their future and their plans for having children. It plays a role, as one important factor among several others.

Our main argument, however, builds on our earlier conclusions: in grappling with the factors that help to shape young adults’ interest in having children, non-economic factors – in this case, the sense of resilience and well-being – are more important. And this should lead us to ask whether we are doing everything we should as a society to ensure young people feel healthy, confident and well-supported.

There is perhaps a risk that our society’s view of youth is clouded by a sense of reverse ageism. It seems natural to imagine young adults as vibrant and optimistic as they face the future, and to assume that it is only as you move into middle- and old-age that life starts to wear you down. But the survey results tell a different story. As our final table (below) shows, economic security, resilience and well-being scores are all higher for Canadians in their retirement years than for younger age groups.

Appendix: additional figures

About the data

The data in this post are from the seventh wave of the Survey on Employment and Skills. This survey is conducted by the Environics Institute for Survey Research, in partnership with the Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University and the Future Skills Centre. The 7th wave of the study consists of a survey of 5,855 Canadians age 18 and over, conducted between May 30 and July 4, 2024, in all provinces and territories. It was conducted both online (in the provinces) and by telephone (in the territories). More information about the survey is available on the Environics Institute website. The authors are solely responsible for any errors of presentation or interpretation.

The Survey on Employment and Skills is funded primarily by the Government of Canada’s Future Skills Centre / Le sondage sur l’emploi et les compétences est financé principalement par le Centre des Compétences futures du gouvernement du Canada.

What is the Environics Institute for Survey Research? Find out by clicking here.

Follow us on other platforms:

Bluesky: @parkinac.bsky.social

Twitter: @Environics_Inst or @parkinac

Instagram and Threads: environics.institute

Cover photo credit: Leah Newhouse

It is important to note that the subsamples to whom this question is asked differs across surveys. The main difference in the survey covered here is that the question is asked only to those between the ages of 18 and 44 who are not parents and who are in the labour force.

The resilience scale combines four questions asking how often someone feels hopeful about the future, confident in their abilities when faced with challenges, able to bounce back after hard times, and that they have people to depend on when needed. The well-being scale combines four questions covering self-reported physical and mental health, the extent of work-life balance, and job satisfaction. The economic security scale includes three questions covering expected personal financial situation in the next six months, whether it is a good or bad time to find a job, and sense of income adequacy. All three scales were evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis.

Since the well-being scale includes a question asked only to those currently employed, the analysis that follows is based on a subsample that excludes people who are in the labour force but who are unemployed.

A decision tree is a simple predictive model that makes decisions by asking a series of if-then questions about the data. For example, “is the respondent over 50?” followed by “is the respondent a woman?” Each tree on its own can be noisy or overly sensitive to the data it's trained on. A random forest improves accuracy by building hundreds of such trees, each on a different random subset of the data and variables, and combining their predictions, typically by majority vote for a categorical outcome.